Imagine you're trying to figure out if a new fertilizer truly helps plants grow taller, or if a groundbreaking drug genuinely improves patient outcomes. How do you cut through the noise, the inherent variability, and the countless factors that could muddy your results? The answer, surprisingly elegant and profoundly powerful, lies in randomization for data analysis and testing data validity.

Randomization isn't just a statistical trick; it's the bedrock of robust scientific inquiry, a method that empowers researchers to draw trustworthy conclusions by neutralizing biases and unraveling true effects. It transforms a chaotic world of variables into a controlled environment where real insights can emerge. From the clinical trials that shape modern medicine to the rigorous data analysis that informs policy, understanding and applying randomization properly is non-negotiable for anyone serious about valid, defensible results.

At a Glance: Your Guide to Randomization

- What it is: A systematic approach using chance to assign subjects to groups or to re-sample existing data.

- Why it matters: Eliminates selection bias, balances unknown confounders, and forms the basis for valid statistical inference.

- Two main flavors:

- In Study Design (e.g., Clinical Trials): Assigning participants to treatment or control groups randomly to create comparable cohorts.

- In Data Analysis (Randomization Tests/Permutation Tests): Re-shuffling observed data to generate a null distribution for hypothesis testing, especially useful when traditional assumptions are violated.

- Key benefit: Builds confidence that observed effects are due to the intervention or factor being studied, not lurking biases or statistical artifacts.

- The Big Takeaway: Randomization is your most potent tool for establishing causality and ensuring the trustworthiness of your data-driven decisions.

Why Randomization is Your Data's Best Friend (and Scientific Shield)

At its heart, randomization is about fairness. It's the scientific equivalent of flipping a coin to decide who goes first – ensuring no hidden preference, conscious or unconscious, sways the outcome. When applied to data analysis and testing data, this simple principle becomes incredibly sophisticated, providing two distinct yet complementary superpowers:

- Neutralizing Bias in Study Design: In experiments, especially those involving human subjects like clinical trials, randomization is the ultimate shield against selection bias. It ensures that the groups being compared are, on average, similar in every way except for the intervention they receive. This isn't just about balancing known characteristics like age or gender; crucially, it balances unknown factors that could also influence the outcome, making any observed differences far more likely to be due to your intervention.

- Unlocking Robust Statistical Inference: Beyond designing fair experiments, randomization provides a powerful, often assumption-free, way to analyze data. Randomization tests (also known as permutation tests) allow us to assess hypotheses directly from the observed data itself, freeing us from the shackles of theoretical distributions that might not fit our real-world data.

Together, these applications ensure that your data validity stands on firm ground, allowing you to move from mere correlation to a much stronger claim of causation. It’s the difference between guessing and knowing.

Randomization in Action, Part 1: The Statistical Powerhouse (Randomization Tests)

Sometimes, your data doesn't play nice with traditional statistical tests. Maybe it's not normally distributed, your sample size is tiny, or the variances aren't equal. In these scenarios, parametric tests (like a t-test or ANOVA) can lead you astray, giving you false confidence or missing genuine effects. That's where randomization tests step in, offering a remarkably robust, non-parametric alternative.

What are Randomization Tests? A "Shuffle & See" Approach

Think of randomization tests as a direct, empirical way to challenge the null hypothesis. Instead of assuming your data fits a specific theoretical curve (like the bell curve), you ask: "How likely is it to see my observed result if there were no real effect in the data, purely by chance?"

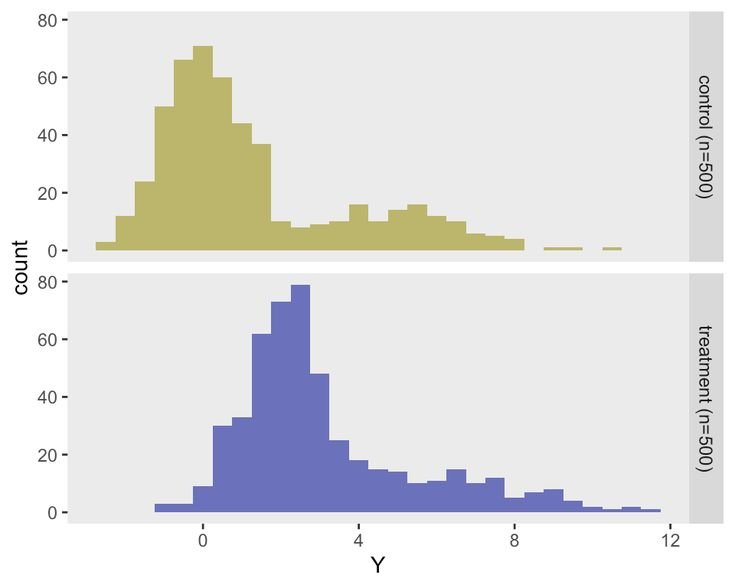

To answer this, you repeatedly "shuffle" or "rearrange" your existing data in ways that are consistent with the null hypothesis (e.g., that treatment and control groups are interchangeable). For each shuffle, you calculate your test statistic (e.g., the difference in means). By doing this thousands of times, you build a unique distribution of test statistics directly from your own data. This distribution then shows you what a "chance" outcome looks like, providing a powerful baseline against which to compare your actual, observed result.

When to Bring Out the Shuffler: Key Advantages

Randomization tests are a lifesaver for several common data analysis dilemmas:

- Non-Normal Data: Your data doesn't need to conform to a beautiful bell curve. These tests work regardless of the underlying distribution.

- Small Sample Sizes: While traditional tests struggle with limited data, randomization tests derive their power from the observed values, making them incredibly useful for small cohorts.

- Complex Test Statistics: You're not limited to standard means or medians. You can define almost any meaningful test statistic for your specific research question.

- Robustness: They are less sensitive to outliers or unusual data patterns because they rely on the data's inherent structure, not a pre-defined theoretical model.

- Transparency: The logic is intuitive: if your observed effect is very rare under thousands of random shuffles, it's probably not due to chance.

How They Work: The "Shuffle & See" Methodology

Let's break down the steps, often called permutation testing:

- State Your Hypotheses: Clearly define your null (H0: no effect) and alternative (HA: there is an effect) hypotheses.

- Example: H0: The new fertilizer has no effect on plant height. HA: The new fertilizer increases plant height.

- Calculate Observed Test Statistic (T_obs): Compute your chosen statistic (e.g., the mean difference in height between fertilized and unfertilized plants) from your original dataset. This is your benchmark.

- Generate a Permutation Distribution: This is the core step.

- Shuffle: Randomly reassign the data labels (e.g., "fertilized" or "unfertilized") to the observed plant heights. Imagine you have 10 plant heights and 5 were fertilized, 5 weren't. You randomly pick 5 heights to be "fertilized" and the remaining 5 to be "unfertilized," irrespective of their original group.

- Re-calculate: For each shuffled dataset, compute your test statistic (Ti).

- Repeat: Do this thousands of times (e.g., 10,000 or more). This process is known as Monte Carlo sampling when you don't calculate all possible permutations (which can be computationally intensive for larger datasets). For small datasets, you might perform a complete enumeration of all possibilities.

- Compute the p-value: Your p-value is the proportion of these shuffled test statistics (Ti) that are as extreme or more extreme than your observed test statistic (T_obs).

- For a one-tailed test:

p = (1/N) * sum(I(Ti >= T_obs)) - For a two-tailed test:

p = (1/N) * sum(I(|Ti| >= |T_obs|)) - Where N is the number of permutations, and I(.) is an indicator function (1 if true, 0 if false).

- Make a Decision: Compare your p-value to your chosen significance level (alpha, typically 0.05). If p < alpha, you reject the null hypothesis, concluding that your observed effect is statistically significant and unlikely due to chance.

- Report Findings: Clearly explain your methodology, the number of permutations, and your interpretation.

Real-World Impact: Where Randomization Tests Shine

Randomization tests aren't just theoretical constructs; they have practical applications across countless disciplines:

- Biomedical Research: Validating treatment efficacy in smaller clinical trials, or when outcomes like gene expression levels might not be normally distributed.

- Environmental Studies: Assessing the impact of policy changes on pollutant concentrations, especially when environmental data often shows skewed distributions.

- Behavioral Sciences: Evaluating interventions with small groups or when using ordinal (ranked) data, where traditional parametric assumptions might not hold.

- Economics and Social Policy: Analyzing the effects of programs on specific populations, particularly when data might be highly skewed or show unequal variances across groups.

Navigating the Nitty-Gritty: Limitations and Best Practices

While powerful, randomization tests aren't a silver bullet. Keep these in mind:

- Computational Demands: For truly massive datasets, running 10,000+ permutations can be resource-intensive. However, modern computing often makes this feasible.

- Correct Shuffling is Key: The validity of your results hinges on performing the permutations correctly. Ensure you're shuffling in a way that truly reflects the null hypothesis (e.g., only shuffling group labels, not within-group observations that might be correlated).

- Small Sample Caveat: With very small samples, the number of unique permutations might be limited, leading to a "coarse" p-value resolution.

- Best Practices:

- Permutations Galore: Always use a sufficiently large number of Monte Carlo permutations (10,000 or more is a good starting point).

- Pre-registration: As with any rigorous study, pre-registering your analysis plan (hypotheses, test statistics, permutation strategy) adds transparency and credibility.

- Document Everything: Keep meticulous records of your random seeds, methodology, and results.

- Complement, Don't Replace: For certain data types, a hybrid approach, complementing randomization tests with traditional parametric methods (if their assumptions are met), can provide a more complete picture.

- For those working with data and needing to perform random selections or generate sequences, tools like an Excel random number generator can be invaluable for initial data exploration or setting up simple simulations.

Randomization in Action, Part 2: The Gold Standard in Research Design (Clinical Trials)

While randomization tests help us analyze existing data, randomization in study design is about creating the data in the first place, ensuring it's fit for analysis. This is particularly critical in clinical trials, where it's the ethical and scientific cornerstone for comparing treatments.

The Unshakeable Foundation: Why RCTs Rely on Randomization

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) are widely considered the "gold standard" in evidence-based research because they answer one critical question: Does this treatment (or intervention) actually cause the observed effect, or is it just a coincidence? Randomization provides this causal link by fulfilling three vital roles:

- Mitigating Selection Bias: Without randomization, researchers (or even patients) might consciously or unconsciously influence who gets which treatment. For example, healthier patients might be assigned to a new drug, making it appear effective. Randomization ensures that treatment assignments are based purely on chance, preventing this bias. This works best when combined with blinding (patients and/or researchers don't know assignments) and allocation concealment (the assignment sequence isn't predictable).

- Promoting Similarity of Treatment Groups: Random assignment helps balance important characteristics (like age, severity of disease, other health conditions) across treatment groups. Crucially, it also balances unknown confounders – factors you might not even be aware of that could influence the outcome. This ensures that any observed differences in outcomes between groups are attributable to the treatment itself, not to pre-existing differences between the patients.

- Contributing to Validity of Statistical Tests: The act of randomization itself provides a powerful basis for statistical inference (known as the randomization model). This model can be more robust than traditional population model-based inference (which assumes data comes from an infinite population and relies on specific distribution assumptions), especially when those assumptions are violated.

Beyond the Coin Flip: Types of Randomization Procedures

While the simplest form of randomization is like flipping a coin for each participant (Complete Randomization Design, CRD), in practice, particularly for sequential clinical trials, researchers use more sophisticated restricted randomization procedures to ensure a better balance between groups.

- Complete Randomization Design (CRD):

- How it works: Each participant has an independent, equal chance of being assigned to any treatment group (e.g., a simple coin flip for 1:1 allocation).

- Pros: Lowest risk of selection bias due to high unpredictability.

- Cons: Can lead to significant imbalances in group sizes, especially in small trials, potentially reducing statistical power. Rarely used in practical RCTs due to this imbalance risk.

- Permuted Block Design (PBD):

- How it works: Random assignments are made within predefined "blocks" (e.g., a block of 4 participants might have 2 for Treatment A and 2 for Treatment B, randomly ordered).

- Pros: Guarantees near-perfect balance within blocks, mitigating group size imbalances. Most widely used in practice.

- Cons: If block sizes are small and not blinded, predictability can increase, making it susceptible to selection bias.

- Maximum Tolerated Imbalance (MTI) Procedures:

- How it works: These designs cap the maximum allowed imbalance between treatment groups at a pre-defined threshold throughout the experiment. They are generally more robust than PBDs.

- Examples:

- Big Stick Design (BSD): A prominent MTI procedure known for striking a good balance between group size control and maintaining allocation randomness (unpredictability). It offers stronger "encryption" of the randomization sequence, better protecting against selection bias compared to PBDs.

- Biased Coin Designs (BCDs): Adjust the probability of assignment based on current imbalance. If one group has fewer participants, the next assignment might be more likely to go to that group. Efron's BCD is a classic example.

- Urn Models: Use a metaphor of drawing colored balls from an urn, adjusting the number of balls for each treatment based on previous assignments to maintain balance.

The Delicate Dance: Balance vs. Randomness

Choosing the right randomization procedure involves a crucial trade-off:

- Balance: Ensuring equal or near-equal numbers of participants in each group. This is vital for statistical power and preventing chronological bias (where patient characteristics change over time).

- Randomness (Unpredictability): Ensuring that future treatment assignments cannot be predicted. This is paramount for preventing selection bias.

Highly restrictive designs (like PBDs with very small, known block sizes) maximize balance but compromise randomness, making them vulnerable to prediction. Less restrictive designs (like CRD) maximize randomness but risk imbalance. MTI procedures like the Big Stick Design offer a smart middle ground, providing good balance while maintaining strong unpredictability.

Making Smart Choices: A Roadmap for Clinical Investigators

Selecting the ideal randomization procedure isn't a one-size-fits-all decision. A systematic evaluation is key:

- Sample Size: Small to moderate studies demand exact final balance. Larger trials can tolerate more randomness without significant power loss.

- Recruitment Period: Long-term studies benefit from designs that balance assignments over time to mitigate chronological bias (e.g., changes in patient demographics or concurrent treatments over the study duration).

- Level of Blinding (Masking): In open-label studies (where participants and/or investigators know the assignments), designs with strong encryption (like MTI procedures) are essential to minimize predictability and selection bias.

- Number of Study Centers: Multi-center trials often use stratified randomization to ensure balance within key subgroups or across different study sites.

- Calibration of Design Parameters: Fine-tune parameters (e.g., the maximum imbalance threshold in BSD, block size in PBD) to achieve desired statistical properties. Monte Carlo simulations can help evaluate how different choices impact Type I error rates, power, and bias under various scenarios.

- Data Analytic Strategy: Pre-specify your planned statistical analysis (e.g., parametric vs. non-parametric tests, covariate adjustment). Decide whether your inference will be based on the population model or the more robust randomization model.

What Can Go Wrong? Pitfalls and Protections

- Selection Bias: If investigators can predict assignments, they might inadvertently (or intentionally) assign certain patients to specific groups, skewing results. MTI procedures like BSD offer superior protection by keeping assignments less predictable.

- Chronological Bias: If patient characteristics evolve over the course of a long trial (e.g., sicker patients recruited later), and your randomization doesn't balance groups over time, this can confound results. Randomization-based tests can help maintain validity even with unknown time trends, and covariate-adjusted analysis can be very effective if the changing covariate is known.

- Small Sample Woes: In very small RCTs (e.g., fewer than 10 patients), the choice of randomization procedure can significantly impact the randomization-based p-value and thus the trial's outcome. Upfront agreement with regulators on both design and analysis is crucial.

Your Toolkit: Actionable Insights for Robust Clinical Trials

- Embrace Randomization-Based Tests: Consider them robust and valid alternatives to likelihood-based tests, especially when traditional model assumptions are questionable.

- Opt for MTI Procedures: The Big Stick Design (BSD) is an excellent choice for balancing treatment assignment while maintaining unpredictability and strong encryption against selection bias.

- Always Consider Covariate Adjustment: If you have known prognostic factors (covariates) that might change over time or influence outcomes, adjusting for them in your analysis can significantly improve power and reduce bias.

- Prioritize Agreement for Small RCTs: For studies with very limited participants, meticulously plan your randomization design and analysis strategy, and seek early agreement with regulatory bodies.

Bringing It All Together: Randomization for Robust Decisions

Whether you're crafting the design of a groundbreaking clinical trial or sifting through complex observational data, the principles of randomization are indispensable. It’s the cornerstone of sound empirical research, transforming guesswork into reliable knowledge.

By understanding and correctly applying randomization—both in assigning treatments and in analyzing your data—you gain the power to:

- Eliminate doubt: Your findings are less likely to be dismissed as mere artifacts of flawed methods.

- Enhance credibility: Your research gains scientific rigor and is taken seriously by peers and stakeholders.

- Make better decisions: From public health policies to product development, decisions based on randomized evidence are inherently more reliable.

In an age of increasing data and information overload, the ability to discern truth from noise is more valuable than ever. Randomization provides that clarity, ensuring that your data analyses lead to truly valid conclusions and that your testing data stands up to the closest scrutiny.

Your Next Step: Elevate Your Data Confidence

Now that you've grasped the profound importance and versatility of randomization, consider where it can strengthen your own work. Could your next experiment benefit from a carefully chosen restricted randomization procedure? Are you currently relying on parametric tests when a randomization test might offer a more robust analysis of your non-normal data?

Dive into your data, review your experimental designs, and ask yourself: Am I truly leveraging the power of chance to uncover the truth? By embracing randomization, you're not just performing a statistical step; you're adopting a fundamental scientific principle that will elevate the validity and impact of all your data-driven endeavors.